*Disclaimer: my opinions are my own

Covered in this article

How salary bands work

What should employees do?

So what should companies do?

Negotiating salaries is a skill that should be taught in college. But since I’ve not seen any courses on the subject, and so many people struggle with it, let me share what I’ve learned over my 20 years in the recruitment industry.

How salary bands work

Every job has a payscale. Some jobs have a set pay, where there is no range. For instance, a person working a temp job filing paperwork may get paid $10.00 an hour regardless of their previous experience. Other jobs have a range. For instance, a manager might be willing to pay more for an experienced engineer than they would for one with no experience, even though they are doing the same job. Now to be fair, there’s an expectation that the experienced engineer will be able to hit the ground running or take less time solving problems or take less of management’s time, etc.

Some less structured companies give managers the freedom to determine job pay with little to no guidelines. Other companies, most publicly traded companies, do market research to set salary bands so that similar roles with similar responsibilities pay similar amounts based on the market. A software engineer in California and one in Texas may be in the same pay band number (also called a pay grade), but the bands cover different amounts due to the difference in market economies. This practice of creating market bands protects the company against inequitable pay claims. Now these ranges can be over tens of thousands of dollars, but it gives a guideline to the manager what they are able to pay.

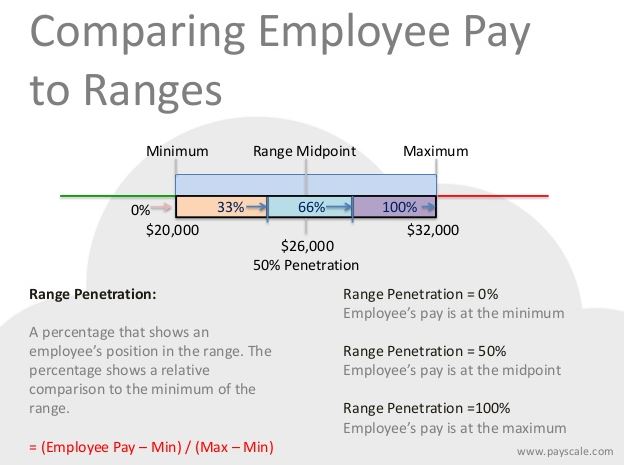

Payscale.com shows it this way

Let’s say a software engineer in Dallas is a band 7, which ranges from $50,000 to $150,000, where 50K is the minimum pay (min), 100K is the mid point (mid), and 150K is the maximum pay (max). One might assume that 100K is the 50th percentile, but it may not be. It may be the 80th percentile. While I assume it’s possible, I have never seen it be the 30th percentile. What this is saying is that companies may be willing to pay the full range for certain exceptions, and they need a wide range to keep them within their own regulations, they have a preference for paying at the front half (min to mid) and let the back half (mid to max) be used for merits over time or internal moves from other roles that may have higher pay in the market, but fall within the same pay band within the company. Most companies target the 50-80th percentiles as the sweet spot in which they do not bring someone into a band over. Also, some companies will not bring an external hire into a band lower than the 30th percentile, except in rare occasions. The most common people in the lower 30% of a band are those who were internally promoted and their salaries were way below the band minimum, so they get a significant increase just to get them to band minimum. This increase is usually 5 to10% more than their prior salary, and thus deemed suitable for a promotion. If their previous band + 5% to 10% increase puts them higher in their future band than minimum, then the company average % increase usually wins, up to 50-80% of the band.

An entry level person in that role (new to the role) with no experience in that role (you can have years of experience in other roles, but if you have none in that role, then it may not help you), will usually be brought in between the 30-50th percentiles. Once you add experience or skills, then you can work your way from the 50-80th percentiles.

Companies typically earn a bucket of funds towards merit increases. If a company did not perform as expected, then those funds were not earned at the rate that was expected. For instance, if a company plans for a 4% merit (which basically counteracts US inflation)

I’ve seen many companies be able to pay externals higher rates than internals. And some companies create processes that inadvertently prevent HMs from paying internals as high as externals, even if they wanted to.

So what does this mean?!? A person looking to make the biggest financial increase, is more likely to make more money leaving their current place of employment and starting work elsewhere than if they stay in their job locally. In fact, the best way to get your work salary up would be to job hop 2-3 times across companies in the same role, then get a promotion, and then do it again.

That’s a problem for corporate America. Employers want to retain employees, especially good ones. The cost of replacing an employee has traditionally been 1X their annual salary.

What should employees do?

Be educated and realistic. Don’t use salary.com and other online salary tools to explain to your boss what you are worth, unless you know how to use it properly. Meaning, average salary anticipates tenure within a role. If you don’t have 5-10 years experience in that exact role and you’re not in the exact location that the online tool quoted, then you’re not comparing apples to apples. Instead, determine what you are worth to your company based on an understanding of your company’s pay grades, in some companies this can be retrieved through HR. If compensation information is not shared internally, then determine your worth based on your improvements and additional value add since your last salary negotiations. After all, at one point, you agreed to making a salary at that company. It may have been the day you were hired, but there was a starting point. Don’t negate your years of experience within that company. Experiential knowledge within a company makes you very valuable to them. Being willing to share your knowledge with others without fear of losing your job makes you even more valuable.

Inform your manager of your salary concerns early, months before you need a raise. And be empathetic with your boss when they cannot get you a raise immediately. More and more employers are only offering promotional level increases during the annual merit cycle. If you wait until then, it’s too late. The merit and promotional process can sometimes begin as early as 3 months before employee notification, and if companies have had challenging net profit years, then they could even be set the year before, when well deserving employees were not able to get the raise that managers fought for.

Be honest with your employer. Let them know you’re looking and other options (if you are), and what you will make outside. Some employers want to do raises, but can only do them if there’s a significant risk if you will leave without one, such as you having an offer on the table. Employers may have a hard time getting a mid-cycle raise approved, but they can often process a counter offer to retain an employee.

If you’re really interested in earning what you’re worth, check out my article on the topic.

So what should companies do?

Unfortunately if everyone followed the tactics above, it would be very hard on companies because they don’t budget for promotional increases. If everyone got a yearly promotion, and fewer people retired, and newer people were requiring more from the start, then corporate inflation would wreak havoc on our economy. But there are things we can do to be fiscally responsible.

First off, treat employees fairly. Fair does not mean oiling the squeakiest wheel because it’s easier on you to make one very vocal person go away, while ignoring the mass of people who don’t have the skill of being bullish. Some people who want raises are too afraid to talk about money, but less afraid to take another job elsewhere – and we’ve already mentioned that’s very costly to the company. Instead, work hard to create fair pay scales where increases within the range are based on specific skills and experience, and make that public knowledge, at least within the company. If employees have a list of 5, 10, or even a hundred things they need to achieve for the raise, they will do it.

Second, once you publish the rules, follow them yourself too. Don’t waive a carrot and then not offer it up when the agreed upon time arises. Don’t cherry pick who will be next, without explaining why to anyone in the running. When passing up an employee for a raise or promotion, give them clear indication of what they need to do, and in what timeframe, for them to see their monetary rewards. And once they do it, act upon it.

One thought on “My guide to compensation in corporate America”